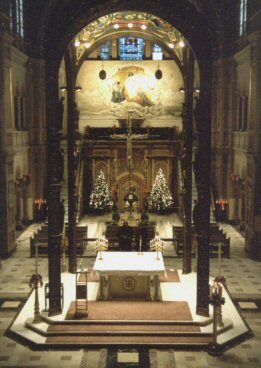

Franciscan Monastery in Washington, D.C.

(Mount Saint Sepulcher Memorial Church of the Holy Land)

Dedication Sermon by Very Rev. L. F. Kearney September 17, 1899

Home Page

"You are the light of the world. A city seated upon a mountain cannot

e hid. Neither do men light a candle and put it under a bushel, but upon a

candlestick, that it may shine to all them that are n the house. So let

your light shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your

Father who is in heaven." Matthew 5:15-16

One

day, seven hundred years ago, Pope Innocent III was pacing to and fro upon the

terrace of the Lateran Palace, when he was accosted by a man clad in coarse and

rugged garb, and destitute of all sign of earthly rank and greatness.

Innocent had never seen the man before, and when the stranger had made known the

object of his visit by

asking permission to found a new religious Order, harassed and perplexed as he

was by the cares of church and state government, the Pope dismissed him with but

scant evidence of respect and consideration. That night the Pope beheld in

a dream a palm which sprang up at his feet and quickly grew from a tiny shoot

into a wide-spreading tree. On the day following, as tradition tells us,

he was made to understand that this tree of rapid growth represented the Order

which the forlorn stranger had craved permission to establish. The

stranger was destined to become one of the world's immortals. His name was

Francis of Assisi. The Order is that of Friars Minor.

Seven

centuries have elapsed since the day when that message from on high determined

the successor of St. Peter to place the seal of his approbation upon the design

of his humble visitor, and to permit him to plant his tree in the garden of

God's church. During those centuries that stately palm has been one of the

noblest ornaments of the garden, conspicuously by its vast breadth and towering

height. True, the winds have swept over it and the lightnings

have played among its branches, and every storm that has threatened the church

of Christ has hurled itself against it with violence and fury. But it has

withstood every shock. The grand old trunk has never bowed before the

storm. It still stands erect, bearing upon it the marks of ages. It

is still charged with the sap of vitality, still supports luxuriant branches and

beauteous foliage, still continues to put forth virent shoots, thus giving

evidence that it is not doomed to die, that it is strong in the promise of a

glorious immortality.

We behold one of the vigorous shoots of that giant trunk when we gaze upon this majestic, monumental monastery, which the children of the old Order of St. Francis, founded early in the thirteenth century, have constructed here in our youthful country at the dawn of the twentieth. And this colossal edifice which they offer to the Most High today quite naturally directs our thoughts to their glorious past; to the magnificent part which they played as chevaliers of the church militant; to the aid and comfort they have lent her in her struggles against the powers of darkness; in the execution of the commission given by her Divine Founder to sanctify the nations.

The religious state is an inseparable adjunct to the church of Christ. The same gospel in which we find the precepts of the Savior contains his counsels - the invitation which He extended to men to do more than observe the law; to aim at perfection by the voluntary sacrifice of personal independence, of earthly riches, and sensual pleasures. And as long as that gospel is recognized as divine, as long as the master is loved and adored by men, there will be found those who, following the inspiration of faith and animated by a sense of gratitude, will imitate His example and tend towards sanctity by the way of His counsels; will make sacrifices of their lives in return for the life He gave for men. Religion must exist. The life, the teachings, and the death of God Incarnate gave to this proposition the nature and dignity of an eternal principle. And, in the strong language of Locadaire, 'Whoever aims at the destruction of a principle seeks to enthrone death, and his labors shall certainly be vain. Nature and society have an incorruptible sap, and they laugh to scorn the speculators who think to change essences, to abolish oaks or monks. Oaks and monks are equally eternal'.

In the early days of the church's existence the fastnesses of the mountains and the wilderness were the homes of thousands who renounced the charms of the world to live in solitude and revel in the sweets of spiritual contemplation. Witness the Pauls, the Anthony, and unnumbered others of other type - 'giants upon the earth', models of heroism, ornaments of humanity. Then came the monasteries of the Benedictines, the Carthusians, Cistercians, and others in which legions of men served God in solitude and silence, and sought in obedience and prayer and labor the exercises of virtues too pure for the world. Theirs was not an active life. Not that it was a life of indolence, but it was not of an apostolic character. Their purpose was to 'live in purity and die in peace'. True, the church which had created their institutes, called them forth at times and charged them with the execution of apostolic work. Thus the sovereign Pontiff sent Augustine to England and brought forth from the well-loved shades of Clairvaux to regulate the affairs of Europe. True, also, their monasteries were in the days of barbarian invasion and long afterward the asylum of letters and learning, which they saved from utter ruin. Yet those institutes had in the design of their founders no reference either to the work of apostleship or the cultivation of divine science; and as the ordinary aim of life the monk of those early days proposed to himself no great nor systematic work except to save his soul.

Heaven inspired two great men almost simultaneously with a new design - the design of combining the cloistral and secular life, combining the monks and the priest, the hermit and the doctor, the contemplative and the preacher. The first of these was a Seraph of Assisi. Before this time the church had her monks, and she had her doctors, and she had her apostles. But as we have seen, the monk was not an apostle nor a doctor. The sons of St. Francis were not to be monks alone, nor doctors, nor apostles exclusively. They were to be all three combined in one - something the world had never witnessed before. Like the recluses of old, they were to meditate in their cells and sing the praises of God in chorus and mortify the flesh by fasts and self-denial, thus making atonement for their sins and the sins of the world, for they were also to labor for the development and perfecting of sacred science, and at the same time to be instruments of the Vicar of Christ and of the episcopacy and the friendly auxiliaries of the secular clergy in sanctifying the souls of the people.

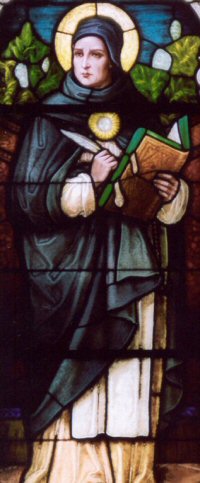

History demonstrates that the union of the three distinct avocations in one life was a happy and congenial union which, far from hampering any one of the three or diminishing its potency for good; added to the efficacy and fruitfulness of each. The spirit of piety, the spirit of asceticism and religious observance flourished within the monasteries of the new institute with as much vigor and splendor as in centuries ago at Monte Cassino, at Cluny, and Clairvaux. And as a consequence the flowers of sanctity budded forth within the walls in the same rich profusion as in the cloisters of ancient days. By the solemn process of canonization the church has placed over eighty of the children of St. Francis upon her altars for the veneration of the faithful, to say nothing of the long line of those whom, by the process of beatification, she has declared to be already among the blessed in heaven; and in countless hundreds of others has been illustrated everything that is great and beautiful and generous and strong in redeemed humanity; and to them may be applied with truth the words of a distinguished modern historian who says of the monks of primitive days that they are 'the representatives of intellectual and moral manhood under its purest and most energetic form'.

At the very time that the Order of St. Francis sprang into existence, Christian Europe was menaced by a danger of the most serious character. Europe abounded at that time in great universities. A violent thirst for learning seized upon the youth of those days, and, though the academies multiplied with marvelous rapidity, the number of students who repaired to each of them was such as to surpass belief. Bologna, we are told at one period of the thirteenth century counted ten thousand pupils, Oxford thirty thousand, and Paris forty thousand. Now, these academies were one and all impregnated by a most pernicious error which threatened to subvert not purity of doctrine only, but purity of morals as well. The recognized master in all of them was Aristotle, and not Aristotle rightly understood, but Aristotle as interpreted by Arabic philosophers, who, under the leadership of Averrhoes, gave a pantheistic tinge to all teaching of the immortal Stagirite.

The intellect of Europe, under the influence of such masters, was trembling on the verge of infidelity and the necessity of the hour was that some powerful hand should be stretched forth to snatch it from ruin. It became evident that the spirit of the schools and the spirit of the cloister should be combined; that the science of the one should be united to the unworldly self-devotedness of the other. The schools were to be Christianized and made to serve the preservation of faith. And in the design of providence this glorious result was to be achieved by the newborn monastic orders.

It is not the spirit of vain boasting or self-gratulation, but simply in deference to history, that I assert that the Friars Preaches, the children of St. Dominic, were the leaders in that mighty movement. Theirs was the glory of producing him, who was the leader of philosophical and theological thought, not only in the thirteenth century, but in every subsequent century as well - St. Thomas of Aquin. From his sainted hands, to use the trite sayings of the schools, the pagan philosopher received the sacrament of Baptism. In his commentaries on Aristotle, written by command of the reigning Pope, he purged the text of the Peripatetic from all that was opposed to faith; and he used his system and method and even his language to synthesize and reduce to order the vast aggregate of the truth of revelation. None will be found to dispute his title as leader in that grand movement of Catholic intellect which marks an era in history. Nor will it be contested that he was most ably seconded by a galaxy of brilliant theologians, who wore the white habit of the Dominicans. But none the less is immortal glory due the Franciscans, who threw themselves into the breach in the same hour of danger and shared with the Dominicans both the shock of battle and the glory of victory. The end of their existence was the salvation of souls, and, as souls could be saved at this juncture only by the defense of the truths which men are commanded to believe, they devoted themselves to the cultivation of scared science and produced an array of doctors - of philosophers and theologians - which were sufficient to immortalize any society or body.

Need I mention the seraph doctor, St. Bonaventure, the bosom friend and intimate companion of St. Thomas, who shared every thought and teaching of the 'angel of the schools'? The wonderful Roger Bacon, who in experimental philosophy was far ahead of his age? The 'irrefutable doctor' Alexander of Hales, who was named by St. Thomas as the safest guide for the student of theology? Duns Scotus, the 'subtle doctor', who has been held up as a worthy rival of St. Thomas Aquinas in the contest for highest excellence in philosophy and theology? All these are names that glitter on the pages of history of scared science. And did time permit, I could add to the list the names of hundreds of other valiant champions of truth among the disciples of St. Francis who bore noble aid to the Church of God in the fierce conflict with medieval rationalism. We find at Oxford, at Cambridge, at Cologne, at Paris, at Bologna, at all the great universities of Europe; and that not in the thirteenth century only, but on down the ages until the sad day when they were led from the professor's chair to the martyr's scaffold, by the ruthless 'reformers' or driven into exile by misguided revolutionists, who saw in the humble but learned friars the staunchest champions of the church which they sought to destroy. We find them during all those ages arguing in the councils and assemblies of Europe. We find them theologians to bishops, confessors to kings, councilors to popes. We find them, in a word, occupying every one of those positions which the church commits only to men of profoundest learning and rarest wisdom.

I spoke of the apostolic character of the Order of St. Francis. I said that the Friar Minor was not only a monk and a doctor, but an apostle, too. His is an Order of Missionaries. The twelve apostles were not bishops only, they were missionaries as well. They carried the glad tidings of the gospel to distant lands. "Their sound went forth into all the earth, and their words unto the ends of the whole world". When the church was duly organized, as intended by her founder, when the nations were converted and received into the fold of Christ, the missionary activity of the bishop was necessarily circumscribed. He was overburdened with a multitude of duties. The administration of his own diocese, the pastoral instructions necessary to his own people, and the functions connected with it, engrossed his attention and that of his clergy. Hence the necessity of another agency for the perpetuation of missionary work - to bring other sheep into the fold. To the religious Orders that holy and noble work was committed. They were raised up by God through the instrumentality of His church, to be the ordinary ministers of apostolic instruction under the jurisdiction and control of the Sovereign Pontiff and the bishops.

The story of the Franciscan's part in this glorious work is told in ponderous tomes. Tartary, China, Japan, the East Indies, the Philippines, these are some of the fields where they have labored and preached and suffered and bled and died. In all these and other lands they have planted the standard of the cross and unfurled to the breezes of Christianity and gathered beneath its fold millions of souls famishing for the knowledge of the true God, and fed them there with the Bread of Eternal Life.

The first priest who set his foot on American soil was a son of St. Francis - the truly great scientist and apostle, Juan Perez, without whose aid Columbus had not perhaps discovered our continent. He was followed by hordes of his brothers as zealous as himself for the diffusion of Catholic truth and of the blessings of religion. They sowed weed of the gospel from ocean to ocean, from Hudson's Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Gulf to Cape Horne. They have truly been a light to the world - a light whose brilliancy can never be obscured by ignorance or jealously or malevolence. The world may be ungrateful. It may refuse to thank them for their superhuman exertions in the cause of religion and civilization. Men may never think of the hardships, the privations they endured, the sacrifices they made to promote the well-being of humanity. No matter. These are all recorded on high in a register that shall shine in eternal splendor, and upon which angles gaze with never-ending pride and joy. And as long as men read history here below, willing or unwilling, they must look upon that city which the Franciscans have built on the mountain top, and which refuses to be hidden. For to quote the words of Pere Lacordaire, 'History had kept the record of their labor. Every coast bears a trace of their blood, the echoes of every shore have awakened by their voices. The Indian, hunted like wild beast, has found shelter behind their gowns. The negro, has still upon his neck the sign of their embrace. The Chinese and the Japanese, separated from the rest of the world, still more by their way of life and their ride than by their geographical position, have sat down to listen to those wondrous strangers. The Ganges has seen them communicate the divine wisdom to his pariahs.

The ruins of Babylon have lent them a stone to rest for a moment, and think of the ancient days as they wipe their dewy brows. What lands or forests have they not explored? What tongues have they not spoken? What wounds of soul or body has not felt their healing hands? Again and again, they have made the circuit of the world under every flag and they have filled with actions the last six ages of the church.

But I hear it said that I am sounding the praises of an institution who glory has departed; recounting the valorous deeds of heroes who are dead and whose race is extinct. Fuit Ilium! The world has advanced, and the institutions of the Middle Ages can have no place in our era. Especially are they condemned to a state of unfitness and uselessness in our country. The conditions here are peculiar. Only 'new things' can avail unto the advancement of religion in America. This ancient Order is not sufficiently supple in the character of its institute to be of service in this wondrous land.

I know not whether to attribute such statements as these to a burst of enthusiasm over something new and untried, yet seemingly full of promise, or to a prejudice against that which has proven itself to be one of the most stable, most powerful, most holy institutions in the Church of God.

Lacordaire said half a century ago, "Never was the world in such dread of a bare-headed man with a wretched woolen cassock on his back". We may say today, never was a country in greater need of bare-headed men with woolen cassocks on their backs than is ours. Never did the spirit of worldliness, forgetfulness of God, contempt of religion, love of sensual pleasure prevail in a greater degree than in our day and country. Never, therefore, was there greater need of living examples of the evangelical counsels, such as this monastery is destined to exhibit to men.

I know the Church is not dependent upon the religious Orders. She is divine. She is indefectible. Her founder may save and perpetuate her by what means He may choose. But I would tremble for her progress and prosperity in our land were the religious Orders doomed to desuetude. Listen to a layman who devoted half a lifetime to the study of their position in the church: "Since the end of the Roman persecution, the grandeur, the liberty, and the prosperity of the church have always been exactly proportioned to the power, the regularity, and the sanctity of the religious Orders. Everywhere and always she has flourished most when her religious communities have been most numerous, most fervent, and most free. It is the monk whom the enemies of the church have most detested and most pursued. Wherever it has been resolved to strike at the heart of religion, it has always been the religious Orders who have received the first blows." (Montalembert)

But such Orders are not 'supple', not flexible in their character - are therefore incapable of adaptation to our age. They are as flexible of the church of which they are a part. 'The church and religious Orders are in the same state as living bodies which preserve their identity, notwithstanding the constant operation of a process by which they are constantly renewed.' Lacordaire was asked why he did not found a new order. He replied: 'I could find nothing newer, nothing more suitable to our times and its wants, than the order I have chosen. It is ancient, but not antiquated, and I can see no necessity of putting my ingenuity on the rack for the sole purpose of dating from yesterday. St. Dominic, St. Francis, and St. Ignatius, when they employed the religious institute for the propagation of the gospel by means of teaching, exhausted all the fundamental combinations of this change. If the history of these Orders is open to objection from our contemporaries, the same may be said of the universal church. That which is doomed to pass away always objects to that which is permanent. The latter can best meet the objection by continuing to exist'.

In vindicating the old I would speak no disrespectful, no disparaging word of the new things of the church. Rather I publicly profess for them that love and reverence which we all should have for any institute which the Church raises up to help her in her glorious work. May all such institutes prosper and flourish! May the day come when they can point out to the world a history as glorious as that of the Order of St. Francis! A history that will tell of a long line of saints and blesseds; of theologians who have been the lights of ecumenical councils and the guides of the popes; of missionaries, whose eloquence has prostrated millions at the foot of the cross!

In conclusion, I extend congratulations to our Franciscan brethren upon the completion of this noble Monastery here beside the youthful Catholic University of America: a university for which I confidently predict a future more splendid and more glorious than that of any one of the academies of bygone days. I express, too, the hope that within the sacred walls of the edifice dedicated today, the traditions of the glorious past may be sustained: that there may be formed saints and doctors and missionaries who shall be like their seraph father and angelic brothers a light to the world worthy of residents of that city built on the mountain edifying and glorifying the Father in heaven by their virtues and their works.